Measuring resistance or voltage with 1 digital I/O

May 23, 2011 10 Comments

Let’s say that you’re trying to measure some resistance, but running low on analog pins. Maybe you’re using a microcontroller (aka micro) that’s purely digital, such as the parallax propeller. Well my friends this post is for you! Let’s consider the fact that nearly all micro’s digital pins trigger at 1/2 of the voltage they micro is being driven at. If we slowly increase the voltage of a micro’s digital input, the micro will consider it HIGH at 2.5+ volts for a 5v micro.

If we use a simple charging RC circuit, we can think of the final voltage as 2.5 volts. What if we have the micro discharge the circuit, so we start at about 0v. After the circuit is discharged the micro will turn the pin to input and time how long the circuit takes to charge to 2.5v. Resistance is easily calculated knowing initial and final voltage, capacitance, and time elapsed.

Math:

At the top is the classical, time domain, voltage of a charging capacitor. Vcap is the capacitor voltage, Eemf is the electromotive force (charging voltage), C is the capacitor’s capacitance, t is the time in seconds, and R is the resistance being solved for.

At the top is the classical, time domain, voltage of a charging capacitor. Vcap is the capacitor voltage, Eemf is the electromotive force (charging voltage), C is the capacitor’s capacitance, t is the time in seconds, and R is the resistance being solved for.

Vcap will be 2.5v when micro triggers, C is .1uF, t is in micro seconds, Eemf is 5v. For arduino, which runs at 5v and digital I/O triggers at about 2.5v. Notice that the 10E-6 cancels out. This is good since Arduino doesn’t have alot of sigfigs to work with during calculations.

Make sure that the time that this circuit takes is reasonable. The time below is in Seconds. Everything else is same as before, R is approximately what resistance is being measured.

variables are same values as above.

variables are same values as above.

Vcap was switched to Vc

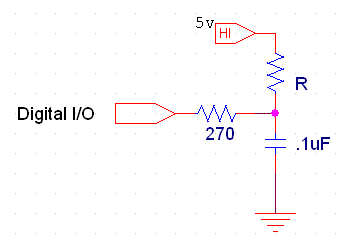

Schematic:

As you can see the circuit is fairly simple. The 270Ohm resistor is to limit current the current as the micro discharges the capacitor. The R is the resistance we’re trying to measure.

As you can see the circuit is fairly simple. The 270Ohm resistor is to limit current the current as the micro discharges the capacitor. The R is the resistance we’re trying to measure.

This circuit is not meant for extremely high sampling rates. If you absolutely need a high sample, then I suggest that you get an ADC chip to do it all for you. Note that if the resistance is high, then you might want to decrease capacitance. If Resistance is very low, then increase capacitance. Only do this if you’re having problems though.

Sometimes the ADC chip is worth it, but if you don’t happen to have one lying around, or if you don’t want to mess around with spi or I2C, then this is a quick work around.

So in this screenshot I had channel 1 (yellow) connected to the capacitor. Channel 2 (blue) connected to a signal pin on the micro. The capacitor’s voltage suddenly drops down when the micro discharges it. When the blue line’s rising edge occurs, that signals the I/O measurement has begun and the pin is set to input. We can then see the blue line’s falling edge occurs when the capacitor’s voltage is at 2.5 volts. As soon as the 2.5 mark is it, the circuit is ready for another sampling. I just had the sampling set to some arbitrary length of time.

Here’s a video of it in action!

Original forum posts

http://arduino.cc/forum/index.php/topic,50642.msg361179.html#msg361179

http://adafruit.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=25&t=19476

Code for the Arduino:

Any analog references are solely for debugging. Remove them when you are confident everything’s working.

Click to download resistor measurement program (pdf)

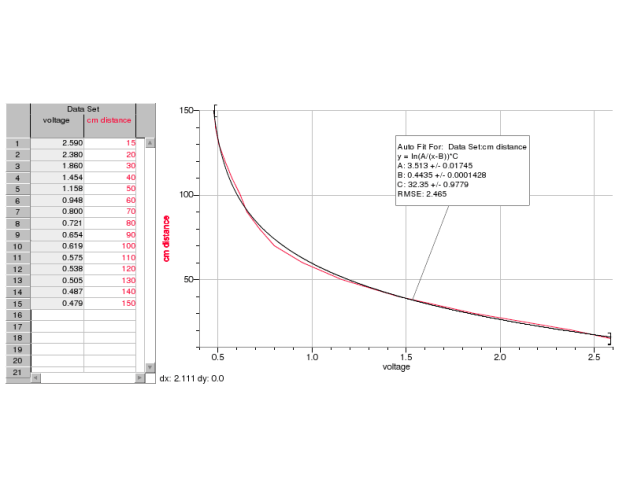

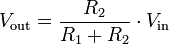

Measuring Voltage using this method: I do like the thought of using 1 i/o to measure nearly any range of voltage, but basically if you’re measuring up to 100 volts, then this method will only be able to measure 50-100 volts. This is because the voltage divider will make the 0-100v into 0-5v, and the pin won’t trigger below about 2.5v. This equation was calculated using Thevenin’s theory. It could also easily be solved using nodal analysis, but then we’d have some calculus to do! I feel as though this is impressive to do very accurate voltage calculations, but it’s a bit complicated and doesn’t work over the full range. An op amp could be added to give a wider voltage measurement range, but this is would require additional pins… and the op amp output won’t like charging capacitors!

Well the voltage calculation was off, but fitting the calculated versus real output results in a linear function with slope almost 1. Interestingly it’s off by a constant.

Well the voltage calculation was off, but fitting the calculated versus real output results in a linear function with slope almost 1. Interestingly it’s off by a constant.

I decided not to investigate why, but it is probably a result of component 10% manufacturing tolerance.

If you decide to give this a shot, then use the top middle schematic with the equation on the very bottom “a” is 2.5 (on the mid left). I suggest you do a function fit of calculated versus real voltage output like I did. Code is extremely similar to the example above. Of course you could just do a function fit for the entire thing since the picture shows the form of the equation.

code for voltage measurement: voltage_measuring_rc